How Digital Fatigue Is Energizing The Resurgence of Magazines

A new ethos among print media publishers underscores how we are looking for more ways to disconnect

To say this country has digital fatigue is an understatement.

We are all bombarded with instant gratification and information overload to the point that we can't discern fact from fiction anymore.

And we've all had enough.

It is why many bibliophiles choose their dusty books over Kindles and why devoted music fans collect vinyl records—a medium that had all but disappeared before most of them were born, at least until its steady resurgence over the past decade.

Because the more connected we are, the more we are looking to disconnect. We are looking for something tactile. Something that gets us away from all the digital noise and distraction, even if it's only for a little while.

With 30 percent of the US population buying physical books compared to the 20 percent that purchased e-books and vinyl sales seeing continued growth after nearly $50 million sold in 2023, it’s probably a safe bet to assume that many are looking for less screen time. It might be the same reasons we are seeing print media once again growing, with newly minted magazines hitting the press with more to come later in the year.

With digital news media facing a paradigm shift as they seek new revenue models to remain competitive, some new standouts have been targeting niche audiences. Upstarts like Puck and Semafor target readers who are seeking a specific facet of news coverage and willing to pony up cash for newsletters, events, and other perks that lie behind paywalls.

Upstart and revitalized print titles are also seeking a similar subscriber base – especially those looking to unplug.

“As a young publication, we wanted people to read front to back."

- Kade Krichko, Ori Magazine

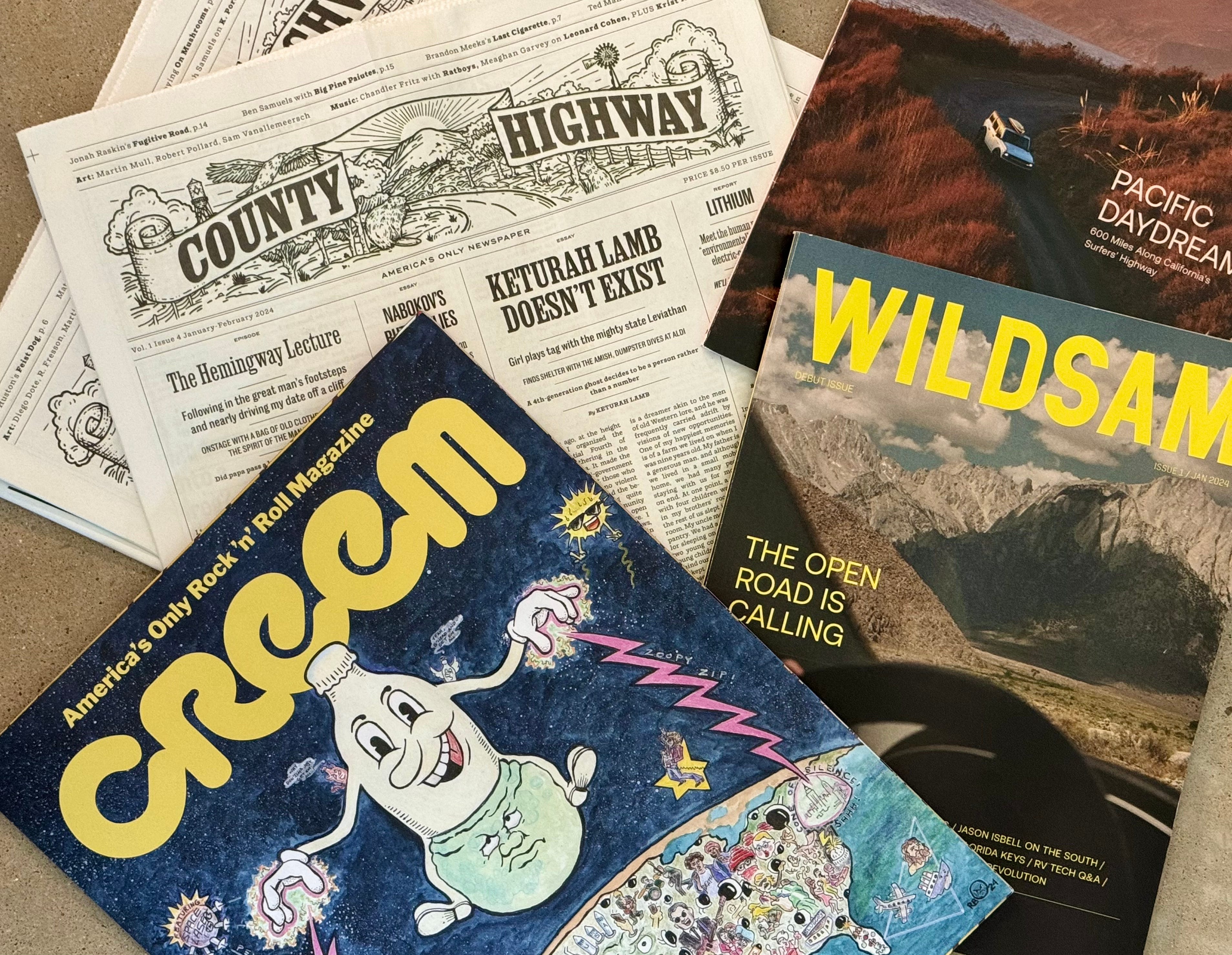

Nearly two years ago, music publication Creem was resurrected from the dead. Instead of publishing their content online, they opted to publish a large tabloid-format magazine quarterly, along with a subscription model that gives readers digital access to the storied title's vast archive, which dates back to the magazine's heyday in the 1970s.

"If we're just talking about pure numbers, you know, some random influencer's TikTok is going to be seen by far more people in one day than my magazine will be seen by people in one year or maybe even ten years. I think that is the fundamental challenge with this," John Martin, CEO of Creem Magazine, said during a recent phone conversation.

"The other side of that coin is that TikTok users are ephemeral, and digital content is made and then goes away. You're pushed down the feed. Whereas the magazine is a real object. We do have content on the website, but we don't do that for free because why would we?”

At first glance, Creem's business model might seem like a recipe for disaster in today's over-digitized landscape, but the opposite has proven true. They have avoided chasing traffic with clickbait and banked on factors like original music reportage and nostalgia. So far, it's paying off. Creem now boasts 12,000 subscribers and was named by Fast Company as one of the most innovative companies of 2024.

"Ultimately, you're brand building. The guy who started Complex [Media], Rich Antonello, always writes a lot about finding your audience and talking to them on the platforms that they're on. Don't be beholden to any one platform, and I think that's really smart…But for us, at least, we said there's zero point in playing the website game and all the bullshit that goes along with it of staffing this website to get high traffic so we can sell ads. And then we're going to have to report on the ads that we're going to sell."

"You may consume a vast amount of content. At that point, why are people going to subscribe to the magazine? They can just get all this content for free and more on the website."

Martin, who previously worked for VICE Magazine and helped launch their popular food vertical, Munchies, says that scaling is essential as long as it's not for the sake of scaling.

"We're looking at starting to put into play products that can only be purchased by subscribers. So, creating this club of scarcity – I think that's really the big takeaway from the digital media world. If there's no scarcity, there's no value," he says.

A newly launched travel magazine is also following the trail of scarcity, hoping to grow a devoted subscriber base.

Ori Magazine, in which its team explores "where we come from and where we're going," recently released its first issue. The title has a subscriber-only business model and aims to build a tight community.

Founder Kade Krichko says he started his biannual magazine after seeing his friend's success relaunching Mountain Gazette and gaining a decent following.

"When that took off, I was getting a little bit disillusioned and thought there were better ways to do this independent print route," Krichko says. "And that's kind of what I tell people with Ori is that it was a project born out of frustration. Frustration for an industry that isn't compensating its creatives, that isn't compensating its creators on time, and that is working with, you know, the same names over and over again and not really providing a platform for younger journalists or journalists that might be outside of the scope of traditional American media."

Ori—short for origin and inspired by a similar word across Latin, Japanese, and Hebrew for rise, opportunity, and light, respectively—was launched at the beginning of the year and is published biannually. This keeps overhead down and encourages what Kade refers to on Ori's socials as #slowreadmovement.

"I invested in this idea that people did want to slow down and hold something physical again, and not only doubled down on just print but also reducing the number of issues we put out," he says. "We only put out two issues a year, and that was intentionally semi based on what we've seen with bigger publications that we admire. The New Yorker puts out tons of issues every year, and it's hard to make it from front to back before the next issue comes out. As a young publication, we wanted people to read front to back."

Kade further explains why he decided to go print over digital.

"That was a huge wrestle for a bit there. But kind of saw this momentum of returning to analog," the publisher says." You see it with vinyl; you're seeing people even snatching up VCRs and people revisiting bookstores again. Obviously, Kindles are popular, but some people are, you know, investing in hardbacks again. And even during Covid, we saw a rise in the proliferation of trading cards. So, this idea of holding something again was really appealing to me."

At the beginning of 2024, popular travel book publisher Wildsam expanded its production to include a new monthly magazine that focuses on—you guessed it—travel and road trips across the United States.

“If there's no scarcity, there's no value."

- John Martin, Creem Magazine

In addition to eight print issues per year, they publish four digital issues exclusive to subscribers, allowing each medium to complement the other.

"Print is a physical experience. You're holding it. It's one of the compelling aspects of doing a print publication versus all digital. It's a different experience when you're holding it," Wildsam founder and publisher Taylor Bruce said in a recent interview on Monocle-produced podcast, The Stacks.

He also recalled a staff meeting from 15 years ago when he was working for a publication at Time Inc. as the first iPad was released. The observations of the CEO, who was leading the editorial meeting at the time, led to Bruce's ethos when creating Wildsam books and other titles.

"The way she described it was when you're reading something, whether on a laptop or an iPad or your phone, your posture is slightly different. You're a little bit hunched forward and there's a bit of a research mentality. You're kind of working. When you're reading something in print, you typically are a little bit sort of like more loose. you're leaned back somewhat there's a little bit of a recline it's a bit more leisurely. That always stuck with me."

"It feels different to have something in print than it does digitally. The attention span on digital is seconds, and print hopefully slows you down a little bit. Good things happen when we slow down."

Creem, Ori, and Wildsam are just a few examples, but each highlights a growing demand for slow media.

Magazine publishing's market share is expected to increase by $3.54 Billion (yes, with a B) by 2027. While much of it comes from digital offerings, the growth is also associated with content-specific publications, which have a narrow topic focus or provide coverage of a localized market. Advertisers relish the chance to target their campaigns to a hyper-focused audience.

However, some publishers are banking that the same strategy can reach a wider audience.

Last month, it was announced that the iconic LIFE Magazine, which ceased to print new issues in 2008, was…well…coming back to life.

The photo-centric magazine was a hallmark of American culture throughout the 20th Century. It featured images from renowned shutterflies and authors like Ernest Hemingway, whose book "The Old Man and The Sea" was first published in its pages.

New owners Karlie Kloss and her husband, Josh Kushner, believe that LIFE can bring something back to America's cultural zeitgeist with newly printed issues.

"LIFE’s legacy lies in its ability to blend culture, current events, and everyday life — highlighting the triumphs, challenges, and unique perspectives that define us," Kushner said in a statement announcing their purchase.

One new publication is ignoring the digital landscape altogether.

In 2023, Author Walter Kirn and non-fiction writer David Samuels launched what they call a "magazine in the form of a 19th-century newspaper."

County Highway publishes its broadsheet six times a year and focuses on various news, essays, and other writing, focusing primarily on middle-American Life. You can get a yearly subscription from them directly or purchase issues at a network of book and record stores across the US. What you can't do is find any of their content online.

“The name County Highway is inspired by what we believe is the perfect-sized place for the enhancement of life and art. A county is a chunk of earth big enough to allow for a variety of human types but small enough to get to know a decent number of your neighbors, where they come from, what they’re proud of, what they fear, what they smoke, what they drink, and what they love. Counties are the right-sized places for telling stories,” reads an editor's note on County Highway's intentionally sparse website.

“Inside our newspaper, you will find reports by people who picked themselves up and went somewhere else in the hopes of discovering something new about America and meeting people who are not cookie-cutter copies of themselves…”